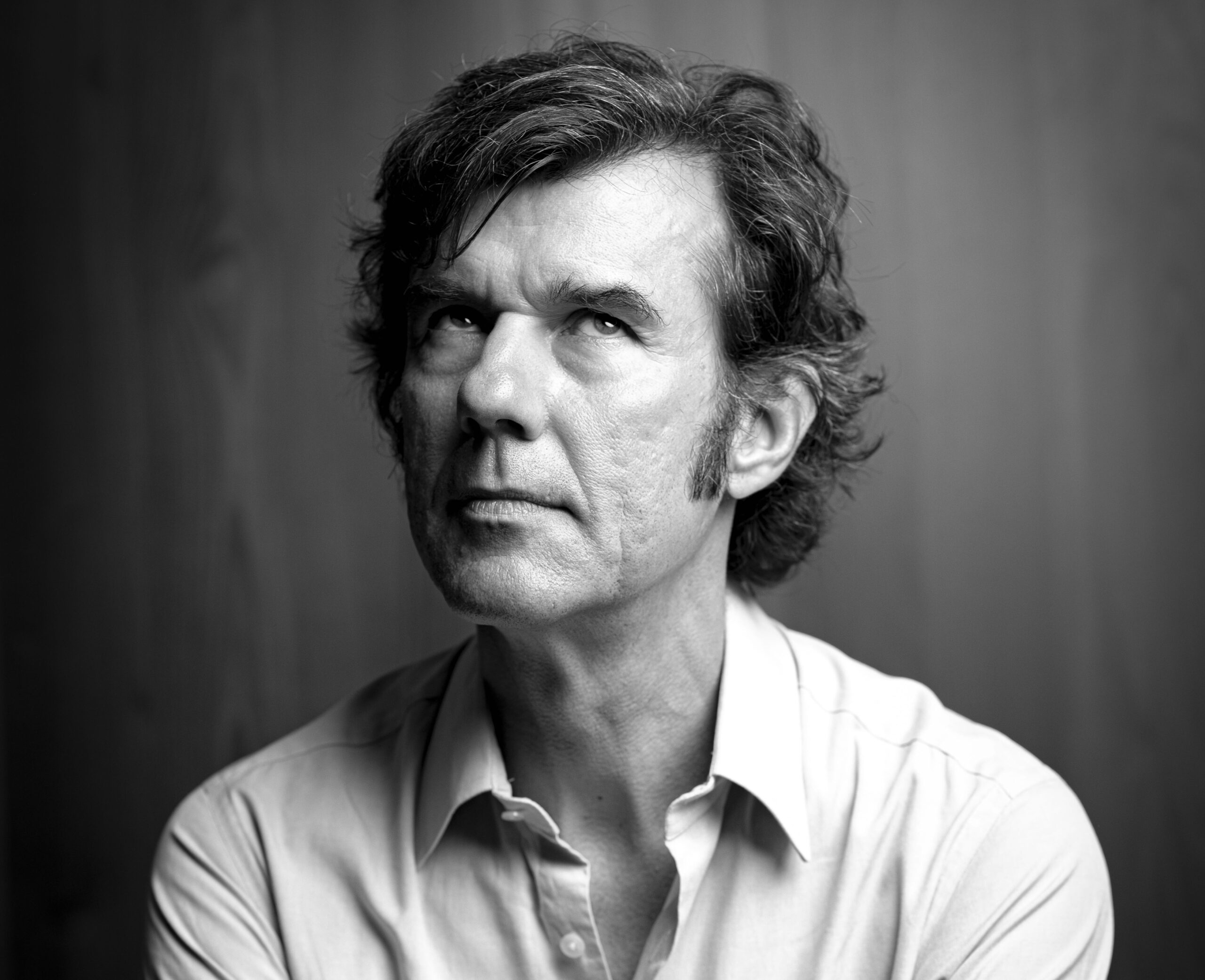

Stefan Sagmeister used his legendary design to shape culture. With artwork at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMa), the designer has won two Grammys, and collaborated with an Avenger’s all-star lineup of pop-culture titans, including Jay-Z, the Rolling Stones, The Talking Heads, and Lou Reed. Born in Austria, Sagmeister gained international recognition in the United States for his distinguished typography, branding, and visual communication that was a staple of his namesake firm Sagmeister Inc., earning him commissions from HBO and the Guggenheim.

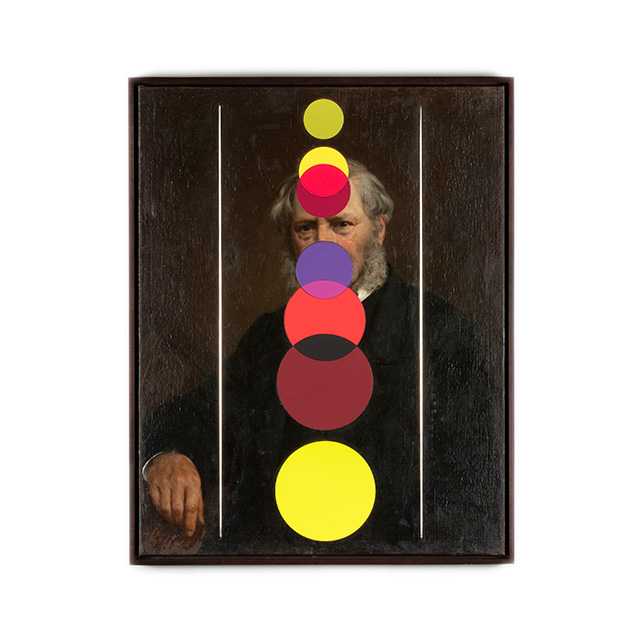

Sagmeister’s latest exhibition tackles the philosophy of history, and sees a return to his roots in Central Europe. After sourcing classic Europe portraits from the 18th and 19th century from Austria, Germany, and Belgium (with a little bit of the United Kingdom and Italy sprinkled in), Sagmeister overlaid modern data visualizations to show a liberal arc to progress. Inspired by the research of Steven Pinker and other scientists, the designer’s “Now Is Better” series debuts on Friday at Patrick Parrish gallery in Tribeca.

Paradox caught up with Sagmeister to discuss the politics of history and why the state of the world isn’t as negative as frequently portrayed.

To what extent have these themes of optimism been layered in your work?

I’ve always leaned towards optimism because it seems like a rational choice if you want to change something. If you have a 50-50 chance of succeeding, those chances will be higher if you approach a problem with positivity.

From a rational perspective, one’s chances increase if approached from a more positive side. The more I looked into timeframes, the more surprised and delighted I became in understanding that you get a completely different viewpoint of the world if you look at the short-term and long-term. Both of these views are correct, of course. There’s much to say about looking at the short-term. But basically all media is now short-term— there is very little long-term media around. The picture that comes out of that is one of negativity because catastrophes and scandals lend themselves well to short-term media.

And that’s why I took on this work. It was a fantastic theme for somebody like me, a communications designer, to create something that concentrates on the long-term. A show like this tries to provide optimism. For considering it’s long-term, it makes sense to create a media that’s long-term. Historic paintings are a fantastic medium because many of the pieces shown at the gallery are 200-300 years old; so they’ve already survived this period, and can make it another few hundreds. And we basically insert forms that on first impression might look like abstractions, but are ultimately bigger visualizations into these historic canvases.

What was the process of sourcing these canvases?

The very beginning of this series, I actually got from the attic in the house where I grew up in; it was from my great, great grandparents who had an antique store in the western part of Austria. But there were only a number of those paintings still there available, but the very first ones came from there. And since then, I’ve been buying these 18th and 19th century paintings at small auction houses in Central Europe, mostly Austria, Germany, Belgium, a little bit UK, a little bit France. Holland, a little bit northern Italy. But I try to concentrate on Central Europe because that’s my culture. That’s what I know.

What was the thought process of choosing which statistics to overlap over each piece?

The process is extremely enjoyable, and extremely different from the process that we applied when we did an album cover. This is strangely much more akin to writing a song. We have all these elements; the historic painting, the form, the color, that some idea can stem from, and often it’s a combination of all of them. With bands in the studio, a song can develop from a section of a lyric or a bass leg, or rhythm section, or from or guitar solo. And this is sort of similar.

I try not to be too much on the nose. I could look for a still life that has bread, and then talk about poverty. And I think that when these things are too similar to each other, they don’t allow the mind to wander anymore. So I’m much more comfortable when those two are a bit further apart, but still are connected. And I think that there is one in the Patrick Parrish Gallery, where it’s a portrait of an 18th-Century woman and we talk about how female rights have developed in the past 200 years. But in general I don’t try to have them too much on the nose.

It’s important to let viewers have the room to come to conclusions, rather than have them exist in a highly regulated framework.

Exactly. And we will have the data in the gallery, but on a separate sheet that you have to go look for if you’re interested. But I also don’t mind at all if someone has their own interpretation in there, and basically ignores the data that I build the thing on. That is completely fine with me.

I really think of these things as design, but because they’re hanging in the gallery, they definitely have much more freedom than the one dimensionality that would be used in, let’s say… a beer ad. A beer ad does not leave a lot of room for the imagination. This is different.

Public Education Spending in developed nations, as percentage of GDP, 1880 – 2000

Steven Pinker is a source of inspiration for this series, in terms of his philosophy toward history. Did you two have any discussions as you put this series together?

He actually wrote the foreword for the book that we are going to publish this fall. I got to know his work and got to hear him talk at TED. We were one time in a group there with the founder of TED to look at the future of the organization; it was a small group in California and we got to talk there. We’re connected and he has one of my prints. The work is based on a number of good scientists, but he would be among the most important ones.

What is your philosophy of history? The very nature of the work is a classical liberal approach that views history as something that does get better over time, as opposed to some people who view history as these neoreactionary cycles. Is it as clear cut as that or is there any room for the latter component?

I think ultimately every piece of progress will by design have side effects that are not obvious when that progress is happening. Those side effects can be very negative. So, from that point of view, progress, of course, is not linear; it’s not a curve that always goes up. I think there’s always a step backwards that then has to be solved in order for progress to continue again.

But I do believe very much that it is much better for me to be alive now, than it would have been 200 years ago; and the person who was alive 200 years ago was much better off than the person who was alive 500 years ago. And there is very, very good evidence for that.